Woodrow Wilson and Election of 1912

|

Profiles

* Political Thought * Colonial Government * Revolution * Constitution * Birth of Party Politics * War of 1812 * James Monroe: "Era of Good Feeling" and Monroe Doctrine * Jacksonian Democracy * Regional Conflict and Compromise * 1860 Election of Abraham Lincoln * Civil War 1861-62 * Civil War 1863-65 * Reconstruction and Impeachment of President Johnson * Gilded Age and Progressive Era * 1912 Election of Woodrow Wilson * 1916 Election and World War I * Women's Suffrage * Depression and 1932 Election of Franklin D. Roosevelt * Prelude to World War II * Pearl Harbor and Mobilization * World War II: European Theater * World War II: Pacific Theater * Atomic Bomb and End of World War II * 1948 Truman-Dewey Election * 1960 Kennedy-Nixon Election * 1964 Johnson-Goldwater Election * Civil Rights Movement * Vietnam: Evolution of the American Role * Vietnam: Kennedy Administration and Intervention * Vietnam: Johnson Administration and Escalation * Vietnam: Nixon, Ford and Fall of South Vietnam * 1968 Humphrey-Nixon Election * Watergate Scandal and Resignation of President Nixon * 1976 Carter-Ford Election * 1980 & 1984 Reagan Elections * Clinton Impeachment * 2000 Bush-Gore Election * War in Iraq * 2008 Obama-McCain Election * 2016 Trump-Clinton Election |

Woodrow Wilson shown while serving as governor of New Jersey in 1911. Image: Wikimedia Commons/hoppyh Woodrow Wilson shown while serving as governor of New Jersey in 1911. Image: Wikimedia Commons/hoppyh

As the governor of New Jersey elected in 1910 after serving as president of Princeton University, Woodrow Wilson had, much like Theodore Roosevelt and other progressives in both parties, pushed for electoral and economic reforms. In his brief period as governor, he signed laws mandating direct party primaries for all elected officials in the state; requiring candidates to file campaign financial statements and limit campaign spending; and outlawing corporate contributions to political campaigns. Wilson also supported passage of a workers' compensation law to assist workers killed or injured on the job and creation of a commission to regulate public utilities and review the rates they charged to their customers.

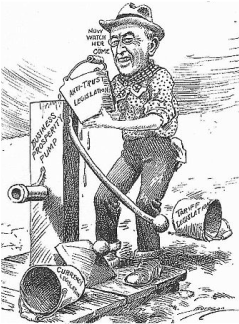

"Pump 1913" cartoon by Clifford K. Berryman depicting Wilson's success in enacting economic stimulus and regulatory measures during his first year in office. Image: National Archives "Pump 1913" cartoon by Clifford K. Berryman depicting Wilson's success in enacting economic stimulus and regulatory measures during his first year in office. Image: National Archives

At the time Wilson was governor, the New Jersey state constitution limited governors to a three-year term and barred standing for a successive term in the next election. So it was not surprising that he was receptive to those urging that he seek the presidency in 1912, only the second year after he had been inaugurated as governor.

1912 Election Wilson's nomination as the Democratic presidential candidate and his subsequent election owed much to political luck. At the party convention in Baltimore in June 1912, progressives divided their support between Speaker of the House Champ Clark of Missouri and Wilson. For fourteen ballots, Clark held a comfortable lead, but was unable to reach the two-thirds majority to secure the nomination. Most of the remaining delegates backed Governor Judson Harmon of Ohio, a moderate supported by key party bosses, and William Jennings Bryan, three-time candidate for President, who continued to have a base of loyal followers in the party. When the bosses of New York's Tammany Hall machine shifted their support to Clark, Bryan countered the move by asking his delegates on the fourteenth ballot to vote for Wilson. The shift later allowed Wilson to gain the lead on the twenty-eighth ballot, but maneuvering continued until his managers agreed to a deal with the leaders of the Indiana machine to give Governor Thomas R. Marshall the vice presidential nomination, finally resulting in Wilson's nomination on the forty-sixth ballot. Yet when the Republicans subsequently held their convention in June, their own divisions proved to be even more damaging than those demonstrated at the fractious meeting of the Democrats. Former President Theodore Roosevelt, who had split with his successor William Howard Taft over what he viewed as Taft's departure from progressive policies, had won a series of party primaries which gave him a lead over Taft in the competition for delegates. At the convention, however, Taft backers were able to exclude most of the Roosevelt delegates by rejecting their credentials. Angered by the tactics, Roosevelt refused to allow his name to be submitted for nomination, thus giving Taft an easy win on the first ballot, running on a ticket with his incumbent Vice President, James S. Sherman of New York. Roosevelt's enraged supporters walked out of the Republican convention, reconvened across town to create a new party, the Progressives, and nominated Roosevelt for President and California Governor Hiram Johnson for vice president. In his speech before the delegates, Roosevelt rallied the crowd by declaring he would "stand at Armageddon and battle for the Lord" and that he felt "as strong as a Bull Moose," thus giving the Progressive Party the popular nickname which many would use in the coming campaign. In the general election campaign, one of the few points of difference between the Democrats and Progressives was Wilson's advocacy of the complete breakup of monopolies, a contrast with Roosevelt's position allowing their continuance under strict regulation. The Democratic platform also backed limits on campaign contributions by corporations, tariff reductions, new and stronger antitrust laws, banking and currency reform, a federal income tax, direct election of senators, a single term presidency, and the independence of the Philippines. President Taft, after delivering a few speeches, essentially left the campaign to his rivals, with most attention focused on Roosevelt's dramatic appearances and Wilson's more scholarly addresses.  New York Tribune front page published November 6, 1912 reporting on election results. Image: Library of Congress New York Tribune front page published November 6, 1912 reporting on election results. Image: Library of Congress

Despite receiving fewer votes than the Democratic tickets headed by William Jennings Bryan had received in each of his three losses in 1896, 1900, and 1908, Wilson's 41.9 percent of the vote bested Roosevelt's 27.4 percent and Taft's 23 percent. Socialist Party candidate Eugene Debs won 6 percent. In the Electoral College, however, Wilson's victory was more substantial. He won majorities in 40 states with 435 electors compared to Roosevelt's six states with 88 votes. Taft won eight electoral college votes from Utah and Vermont, the only two states that supported him.

First Term

In his first term, Wilson's background as a leading scholar and analyst of American government was reflected in his aggressive use of the presidency to set the nation's policy agenda. Soon after his Inauguration, he called a special session of the Congress to act on cutting tariffs and became the first president since John Adams to appear personally before the two houses to seek action. The legislation which he later signed sharply reduced tariff rates, offsetting the loss in revenue through a new graduated income tax. Wilson also gained passage of additional laws to establish the Federal Reserve Board with authority to set interest rates and control the money supply to lessen the cyclical risk of fiscal panics; to create the Federal Trade Commission to combat unfair business practices and fraud; and to place new controls on monopolistic and price-fixing practices. Wilson's progressive program also included new laws prohibiting child labor; limiting railroad workers to an eight-hour day; and setting up a workers' compensation program for federal employees. He also established the Department of Labor, appointing a former union official as its first secretary. After war broke out in Europe in September 1914, Wilson supported continued neutrality, but also asked for funds to strengthen the military. Next Election of 1916 and World War I |