|

Profiles

* Political Thought * Colonial Government * Revolution * Constitution * Birth of Party Politics * War of 1812 * James Monroe: "Era of Good Feeling" and Monroe Doctrine * Jacksonian Democracy * Regional Conflict and Compromise * 1860 Election of Abraham Lincoln * Civil War 1861-62 * Civil War 1863-65 * Reconstruction and Impeachment of President Johnson * Gilded Age and Progressive Era * 1912 Election of Woodrow Wilson * 1916 Election and World War I * Women's Suffrage * Depression and 1932 Election of Franklin D. Roosevelt * Prelude to World War II * Pearl Harbor and Mobilization * World War II: European Theater * World War II: Pacific Theater * Atomic Bomb and End of World War II * 1948 Truman-Dewey Election * 1960 Kennedy-Nixon Election * 1964 Johnson-Goldwater Election * Civil Rights Movement * Vietnam: Evolution of the American Role * Vietnam: Kennedy Administration and Intervention * Vietnam: Johnson Administration and Escalation * Vietnam: Nixon, Ford and Fall of South Vietnam * 1968 Humphrey-Nixon Election * Watergate Scandal and Resignation of President Nixon * 1976 Carter-Ford Election * 1980 & 1984 Reagan Elections * Clinton Impeachment * 2000 Bush-Gore Election * War in Iraq * 2008 Obama-McCain Election * 2012 Obama-Romney Election |

James Monroe:

|

James Monroe 1758-1831

Image: White House James Monroe 1758-1831

Image: White House

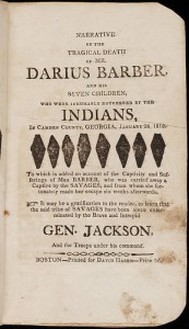

Election of 1816 As he approached the end of his second term, President James Madison announced that he would not run again, following the precedent set by George Washington of serving only two terms. In the caucus of Democratic Republican members of Congress convened to select the party's candidate to succeed Madison, James Monroe, Madison's Secretary of State, was nominated over former Georgia Senator William Crawford. Opposition to Monroe was largely based on his being another potential president from Virginia—with the first four presidents all from Virginia except for John Adams of Massachusetts. In the general election, the Federalists, who had virtually collapsed as an organized party due to their opposition to the War of 1812, did not nominate an official candidate, but Rufus King, a Federalist from New York, ran without the party's formal endorsement and was soundly defeated, gaining only 34 votes to Madison's 183 in the Electoral College. Following his election victory, Monroe commenced a 15-week tour through the New England states, the first presidential tour since George Washington's, and subsequently toured the South and West, setting a model for later presidents in building popular support. After Monroe visited Boston, the city's Columbian Centinel newspaper published an account on July 12, 1817, using the phrase "Era of Good Feeling" to describe the prevailing mood of the country, a label which later would be attached by historians to the period from about 1815 to 1825. The demise of the Federalists as an effective opposition, along with the reduced concern over foreign incursions resulting from the conclusion of the war with Great Britain, brought a renewed sense of national consensus. For a time at least, the end of the war also sparked an economic surge after the years of embargoes and hostilities which had disrupted trade and shipping. Panic of 1819 Nonetheless, there were occasional controversies. Monroe was criticized for what some charged was an inadequate response to the economic crisis known as The Panic of 1819, which resulted in a surge in bank failures, foreclosures and bankruptcies and resulting high unemployment. The economy would gradually recover, but many would continue to question what they viewed as the excessive influence of banks in setting interest rates and lending policies. Missouri Compromise  Title page from book published in 1818 by widow of Darius Barber giving account of killing of her husband and their seven children by Indians in Georgia, along with comment, "It may be a gratification to the reader, to learn that the said tribe of SAVAGES have been since exterminated by the Brave and Intrepid GEN. JACKSON, And the Troops under his command." Image: Early Visions of Florida Title page from book published in 1818 by widow of Darius Barber giving account of killing of her husband and their seven children by Indians in Georgia, along with comment, "It may be a gratification to the reader, to learn that the said tribe of SAVAGES have been since exterminated by the Brave and Intrepid GEN. JACKSON, And the Troops under his command." Image: Early Visions of Florida

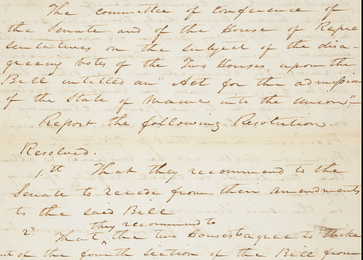

Also in 1819, the emerging conflict over slavery sparked sharp debate in the Congress over the admission of Missouri to the Union as a slave state. The controversy threatened to upset the balance of slave and free states in the Congress, posing risks to the survival of the nation. In retirement, Thomas Jefferson wrote to a friend that the "Missouri question aroused and filled me with alarm...I have been among the most sanguine in believing that our Union would be of long duration. I now doubt it much." To preserve the balance of free and slave states, Congress ultimately crafted what would become known as "The Missouri Compromise," in which Missouri entered as a slave state along with Maine, a newly constructed state formed when Massachusetts agreed to allow its most northern counties to split off to seek admission as the new free state of Maine. The agreement also prohibited slavery in the western territories of the Louisiana Purchase above the 36/30' north latitude line, except within the boundaries of the proposed state of Missouri. Missouri Compromise, Library of Congress Acquisition of Florida For several years, the escape of slaves from states in the deep south to Spanish-owned Florida had been the subject of complaints to Spanish officials. Many slaves found refuge with Seminole Indians, who had launched intermittent raids across the border into the U.S. and who had rejected demands that the fugitive slaves be returned to American owners. In 1818, President Monroe sent General Andrew Jackson, the hero of the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812, to the Florida border, with somewhat vague orders on how Jackson was to confront the problems. Jackson's troops invaded Florida, captured a Spanish fort , took control of Pensacola, and deposed the Spanish governor. He also executed two British citizens whom he accused of having incited the Seminoles to raid American settlements. Jackson's aggressive moves sparked controversy, including a request by Secretary of War John Calhoun that he be reprimanded, but the incursion demonstrated that Spain had little ability to defend its territory. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, who had defended Jackson's actions in Florida, then saw the opportunity to open negotiations with Spain, ultimately reaching an agreement, the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819, in which Spain sold Florida to the U.S. and dropped its claims to the territory sold by France in the Louisiana Purchase. In return, the U.S. agreed to relinquish its claims on Texas and assume responsibility for $5 million that the Spanish government owed American citizens. After the Treaty was approved, in March 1821 Monroe appointed General Jackson as commissioner of the new territory to act as its governor until a territorial government was formed in January 1822. Election of 1820 Monroe's popularity was affirmed in the election of 1820 when, for the first time since the election of George Washington, no opponent challenged the president's election. The few remaining Federalists failed to mount any serious objection to a second term for Monroe and some openly supported him; indeed, former President John Adams, founder of the Federalists, came out of retirement to serve as a Monroe elector in Massachusetts. Monroe was re-elected with all but one electoral vote--a vote withheld by an elector from New Hampshire only due to his belief that George Washington should continue as the sole president to have the honor of being elected unanimously. The Monroe Doctrine The policy which would become known as "The Monroe Doctrine" was set forth in President Monroe's seventh annual message to Congress on December 2, 1823. While its underlying motivations were not directly expressed, it was issued in the context of continuing reports that Spain, perhaps with allies, might seek to reclaim its former colonies in the New World which had gained their independence. Other concerns over colonial expansion came from potential colonial expansion by Russia, which had established a profitable fur trade in Alaska and had extended its presence to the south by building a fort in northern California. To discourage any plans for intrusion in the Americas, Monroe asserted in his message that the European powers were obligated to respect the Western Hemisphere as the United States' sphere of interest. ...We owe it, therefore, to candor and to the amicable relations existing between the United States and those powers to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety. With the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power we have not interfered and shall not interfere. But with the Governments who have declared their independence and maintain it, and whose independence we have, on great consideration and on just principles, acknowledged, we could not view any interposition for the purpose of oppressing them, or controlling in any other manner their destiny, by any European power in any other light than as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States.... Excerpt from "The Monroe Doctrine" in President Monroe's Seventh Annual Message to Congress Although overshadowed by the attention given to the President's bold foreign policy statement, in the same annual message Monroe also announced significant domestic legislative initiatives to establish a national bank with regulatory powers over other banks; a program of federally funded roads and canals; and a protective tariff to shelter the nation's growing manufacturing industry from European competitors. In the following months, all of Monroe's proposals would be enacted in some form. Resources * American President: James Monroe (1758-1831) >> Miller Center, University of Virginia * American Forum - A Virginia Dynasty? James Monroe and the Presidential Elections of 1816 and 1820 >> Miller Center, University of Virginia * James Monroe: A Resource Guide >> Library of Congress * Life Portrait of James Monroe (video) >> C-Span * Missouri Compromise >> Library of Congress * Monroe Doctrine >> National Archives * Papers of James Monroe >> University of Mary Washington Education * The Monroe Doctrine: U.S. Foreign Affairs (circa 1782–1823) and James Monroe (lesson plan) >> EdSITEMENT/National Endowment for the Humanities * Monroe Doctrine: Lesson Plan >> Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History |